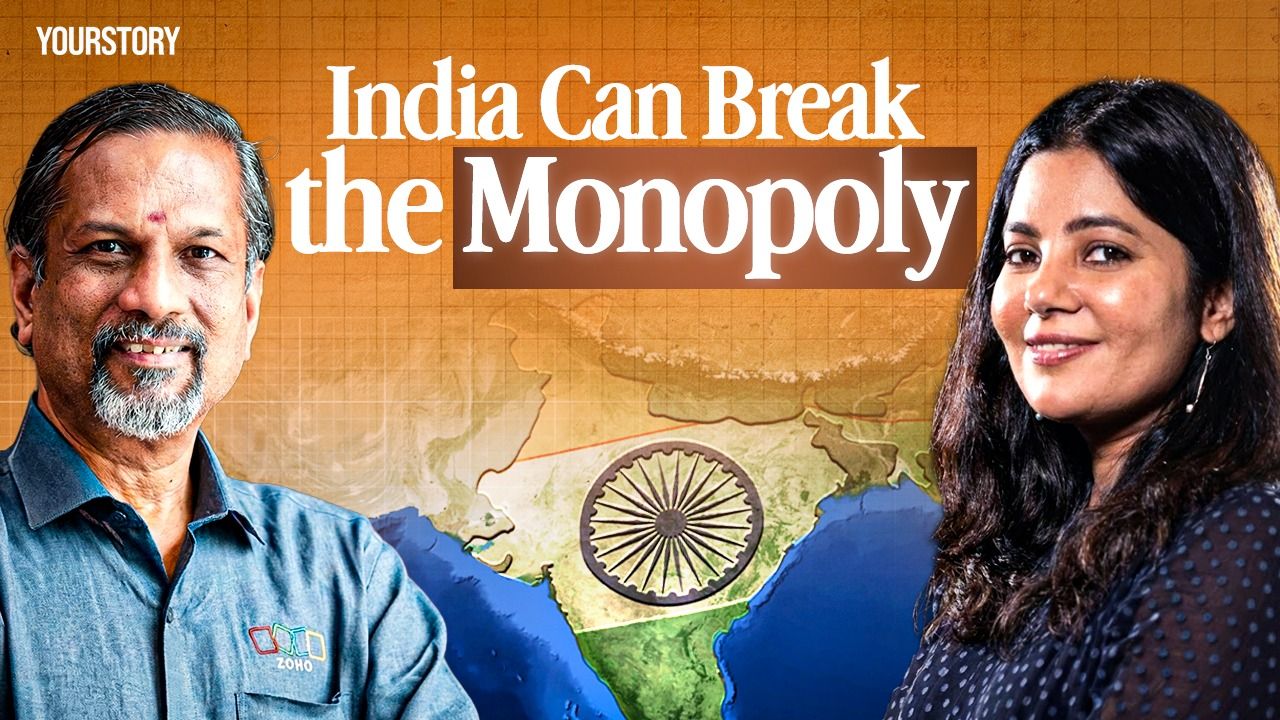

The coming 20 years will decide India’s next 100, says Zoho’s Vembu on building Bharat

“Indians are having fewer and fewer children. In fact, in a state like Tamil Nadu, we are almost in a crisis where the number of babies born every year is dropping rapidly,” he said in a conversation with YourStory Founder & CEO Shradha Sharma. “So, it is on the people who are young today to shape this country.”

But then, he said, it’s also a fact that India is now officially the most populous nation. “We have a special role in the world through sheer demographic weight.” And therefore, it is crucial to adopt a “Bharat-first” approach and to have a vision for the world.

For him, a Bharat-first vision has a philosophical basis. “The essence of Bharatiya (the Hindu philosophy) is both contentment and humility. This is what our saints and philosophers have taught us for millennia,” he said, calling it “an inclusive vision for the world.”

This inclusive spirit, however, is missing in today’s world of technology, he said. “Big Tech is effectively erecting monopolies.”

Vembu said, “If you go to the Integral Coach Factory in Chennai, it was built with Swiss help in the 1950s. They did not, at that time, erect a monopoly and say you pay tax to that monopoly. They gladly shared the technology.”

However, “That spirit has been completely lost.”

India, he said, is the only country that can actually fight what he calls “the East India Company” mode of existence. “This has nothing to do with capitalism or socialism. It has to do with humanism.”

<div class="externalHtml embed" contenteditable="false" data-val="”>

Zoho, which began as AdventNet in 1996, took an unconventional path in 2011 by setting up a development centre in Tenkasi, a rural area of Tamil Nadu. It has since doubled down on this approach of building offices in smaller towns and villages across the country.

“We are not in Tenkasi because we want to sell our stuff here. We are here to make people productive so that they can earn, so that they can participate in the global economy,” said Vembu, who relocated to Tenkasi in 2019.

Sounds of the peacock

Vembu said, though technology plays an important role, in the quest to build it, “I cannot destroy the soil here, destroy the water here, and pollute all of that”. Contentment, therefore, should be “our foundational principle.”

Vembu is up between 330 and 430 am every day without the help of an alarm. He starts working almost immediately: “My brain is active and that’s the two hours when I get the most done.” He notes down ideas, reads papers, and sends them to engineers.

He does yoga for 40 minutes on most days, and sits still, silently on a rock or a creek for 10-15 minutes. He keeps the phone away for at least two to three hours. He takes a short nap in the afternoon and goes to bed at 9-930 pm. That’s his routine.

“I enjoy the actual life,” said Vembu, who occasionally goes for a swim. He rarely watches movies and doesn’t know who the current IPL champion is, likening it to not knowing the “president of Mongolia”.

Being in Tenkasi has added advantages, he said. The cost of living is low, and “I wake up to the sounds of peacocks every day.” He also said, “Everywhere I go here, there’s that instant recognition. That cannot be bought with money.”

That doesn’t mean village life is bereft of problems. “Look at remote villages, transport is a problem. How do we invent better transport? How do we invent cheaper transport? How do we invent health care?”

And technology is needed to solve problems, such as better transport or healthcare in villages, “but you have to put technology in its place in the product framework of life.”

The problems that he mentioned can be solved by “determined entrepreneurs.” Vembu said, “The way I like to say is that there are only 832 districts and you split each district into maybe 20 mandals, we are talking about 16,000 to 20,000. Don’t we have 20,000 determined people who can take root in each of these?”

“And you go down to the panchayat level, there are only 650,000 villages. Do we have 650,000 people, one for every village? You see the numbers actually are not that big compared to our country’s scale now.”

This approach is what is called ‘divide-and-conquer’ in computer science, he said. “You take a massive problem, divide it into sub-problems.” These are what you solve for.

Vembu said, “You cannot look at the scale of this country only from the Delhi perspective or even the scale of Karnataka from a Bangalore perspective. I have a very different perspective sitting here. It’s like the last village. I get a very different perspective on life itself from here. And all those places look remote to me from here, from this perspective.”

He said, “I am connected to the world. But when I read about a bubble in Silicon Valley, to me those are distant, abstract concerns. I am not living through that bubble. So, I can more calmly examine it. To me, a traffic problem is also something I can calmly examine. My traffic jam here is a herd of buffalo crossing the road in the evening.”

Curiosity & philosophy

Vembu said he is happy he is now getting the time to do deep technology work. But why does he do this? It’s not for money – “I have zero interest in it.” He said, “These are all scientific projects driven by that curiosity to explore. And then the philosophical outlook and humility that come from my parents and our spiritual endowment.”

He said he has always been curious about how things work. He applies it in any domain, from seeking to make software better or reinventing education to prevent dropouts (“If you are not interested in this bookish learning, I respect you. Let’s figure out how to you know make you learn without you know saying study, study, study all the time, which a lot of parents do, right?”).

Vembu studied in a school funded by a philanthropist called Jaigopal Garodia. “It was a free education. He helped thousands of children like me at that time. Now, I have to do this to repay my gratitude to him.”

Edited by Sriram Srinivasan

Discover more from News Link360

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.