World Cancer Day: Why psycho-oncology Is changing cancer care

In early 2018, after my treatment for Stage 3 ovarian cancer, I was told that I had reached the triumphant stage called NED (No Evidence of Disease). It was a rare, positivity-fuel day. The baldpate, oppressed bone marrow, and thousands of niggling pains in my body be damned, I thought; the stakes were high, I wanted to live, and I ought to try everything.

The cancer experience is singularly brutal and isolating. Our fundamental building blocks, the body’s cells, go rogue, and addressing all parts of my being made profound sense, including my mental and emotional health. Unlike now, psycho-oncology was not a formal part of oncology departments at all hospitals in 2018. So, I decided to call Vijay Bhat.

Bhat, co-author of My Cancer Is Me: The Journey From Illness To Wholeness (2013), is founder of the organisation Cancer Awakens in Mumbai. Colon cancer in his early 50s brought the former CEO of ad agency Ogilvy & Mather back to India. Now, he is a cancer survivor of 25 years — a “cancer thriver” in wellness-oncology speak.

Registering for the NGO’s mental-emotional support programme was a turning point. The “new normal” was tougher than I had imagined. Part of what Cancer Awakens sherpa, and now my friend and a mentor, Anamika Chakravarty did with me was psycho-oncology. She addressed my emotional and mental stressors, identified in various aspects of my life through an elaborate set of questionnaires, over 23 sessions. I found direction to seek tailor-made solutions from experts. (Bhat himself had combined various models of western mental health solutions as well as ancient healing methods, which he had rigorously researched and experimented with.) Self-awareness acquired new meaning after this slow, empowering experience. I embraced therapy not just as a cancer survivor, but for all my existential coils.

Now, nine years later, ahead of World Cancer Day on February 4, an ad selling a psycho-oncology certification course just popped up on my mobile phone.

At last, a formal field

Studies point to breast cancer incidences in Indian women even in their 20s. Colon cancers in younger populations and lung cancers in non-smokers are rising, too. Both Poornima Sardana and Nishtha Gupta were diagnosed with ovarian cancer in their 20s.

Sardana, 37, pursuing a Ph.D in medical humanities in Melbourne and who lives between Delhi and Melbourne, was diagnosed at 29. “There wasn’t a psycho-oncologist available when I started my treatment, but I went for therapy after my treatment,” she says. “Usually, cancer takes a toll on the mind once the treatment is done and the support systems start becoming faint. That’s when the changes in the body and a sense of loss hit hard.”

In 2019, Gupta, aged 23, was fresh out of IIT Delhi when she was hit with a double whammy of being diagnosed with low-grade serious ovarian cancer and her boyfriend parting ways with her owing to the disease. “After treatment, I developed a kind of OCD (obsessive compulsive disorder),” she says.

The uncertainty and the pain drained her emotionally. “I went to a psychologist later than I should have. At the time, insurance was not covering therapy, which was my concern. Later, I realised, Fortis hospital was providing psycho-oncology free of cost, so I went there, and then continued with another therapist. Some cancer patients go through anxiety, others face depression. In my case, a severe form of OCD made it difficult for me to manage living in Delhi by myself. Psycho-oncology helped me overcome that,” says Gupta, whose family lives in Agra. She now works as a revenue optimisation lead at a company in Lisbon, Portugal. A fitness fanatic, she is a body-positivity advocate on social media and travels around the world — for adventure and new experiences.

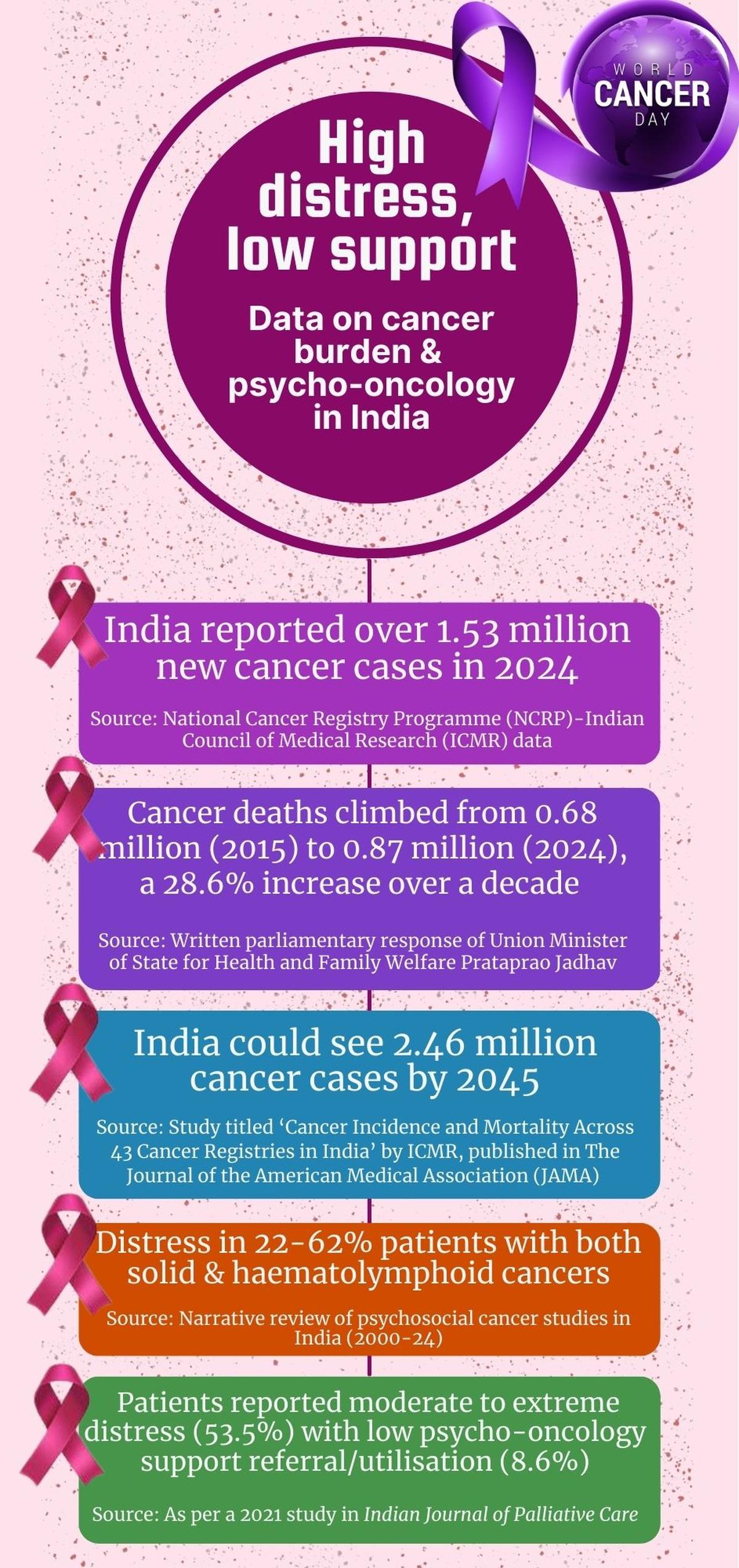

In India, psycho-oncology is finally carrying weight, alongside the changes in the last decade in the cancer treatment landscape, the ecosystems of care and support, and cancer’s burden on the population. While treatment options for different kinds of cancers, especially the most common ones — lung, oral cavity and breast — have expanded, the number of new cases and deaths from the disease continue to rise.

According to the latest (2024) estimates of the National Institute of Cancer Prevention and Research, 2.5 million Indians live with cancer, a jump of 26% in the last three decades; the annual number of deaths is around 0.6 million people. Dr. Sewanti Limaye, director, precision oncology, at Reliance Foundation Hospital and Research Centre, Mumbai, says that part of her work as an oncologist is to be an advocate for prevention and screening. “In India, cancer patients come to us at a late stage. Screening and prevention are the urgent solutions we need,” she says.

Psycho-oncologists in oncology departments may not have far-reaching impact on the burden itself, but it is still a breakthrough. Addressing the mind-body axis isn’t new in cancer care — it was just outside of hospitals, and excluded from oncologists’ prescriptions. Cancer coaching was a domain usually of survivors, who train in holistic or psychological modalities and set up practices of their own to help the newly diagnosed or the new survivor.

Most big hospitals are beginning to embrace psycho-oncology as one part of a multi-disciplinary approach. Dr. Rituparna Ghosh, senior clinical psychologist, Apollo Hospitals, Navi Mumbai, says, “Psycho-oncology supports patients in preserving identity and dignity during illness. It helps individuals to navigate changes in body image, sexuality, fertility, professional roles, and family dynamics. For patients with advanced disease, psychological care facilitates meaning-making, emotional closure, and discussions around goals of care.” Apollo Hospitals runs 14 specialised cancer care centres across India and each one has psycho-oncologists.

Adapting to challenges

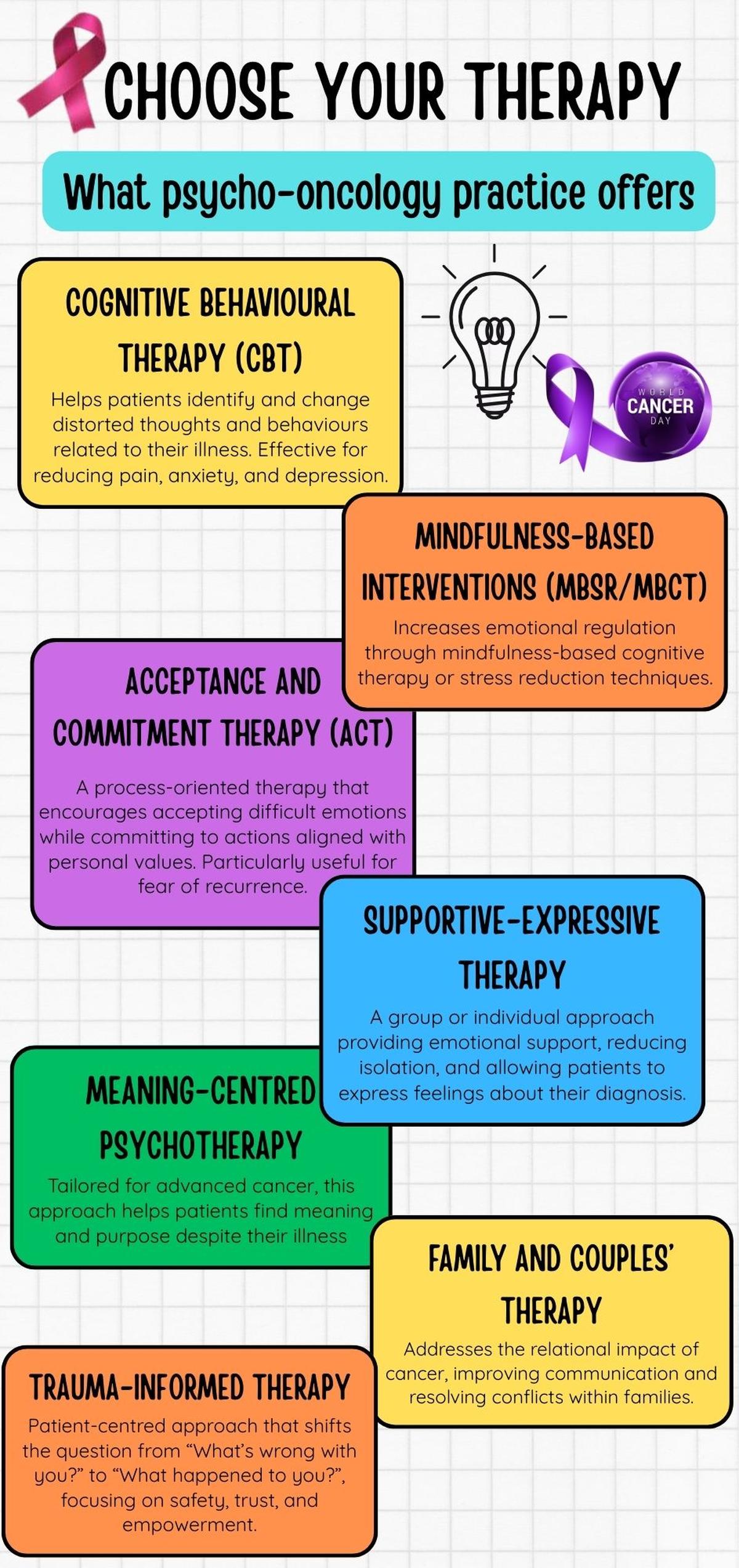

Every patient has a different challenge, and a psycho-oncologist has to adapt depending on what the stage of diagnosis is, their age, and the kind of mental discomfort the patient or survivor is experiencing. Take the most common form of therapy in psycho-oncology, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). After it is recommended as a part of the treatment protocol, the patient and their family, or the patient alone depending on the case, meet the psycho-oncologist, who has to build the patient’s trust in therapy, understand and identify blocks or negative thought patterns, recommend activities and exercises to reframe those thoughts, and change mental-emotional outlook and behaviour.

In my trauma-informed therapy class, we would set a session’s goal, work on techniques such as thought challenges, and be given homework. “Psychological intervention has a direct impact on treatment engagement,” emphasises Apollo’s Dr. Ghosh. “Patients who feel emotionally supported are more likely to attend appointments consistently, follow treatment recommendations, and communicate openly with their healthcare teams,” she says.

Dr. Nikhil Himthani, a medical oncologist at MOC Cancer Care and Research Centre, New Delhi, affirms this shift. MOC is one of India’s growing community-based cancer centres that specialises in chemotherapy and comprehensive oncology care. It has 25 branches pan-India and 19 psycho-oncologists across centres. “In the near future, psychological counselling will no longer be viewed as an optional add-on, but as a critical pillar of evidence-based oncology,” says Dr. Himthani. “Recent data suggests that when we treat a patient’s mind alongside the tumour, it impacts quality of life but also potentially leads to enhanced clinical outcomes.”

Vivek Sharma, founder of Uhapo, a community-centric cancer care platform designed to support patients and caregivers through personalised assistance, says he is beginning to see real changes in patients after counselling has become routine in various hospitals, particularly in Mumbai’s Tata Memorial Hospital. “Most insurance companies are including the holistic and psychological aspects of treatment now. I think the real tipping point will come when every oncologist in India prescribes psycho-oncology as a mandatory step in treatment,” Sharma says.

Globally, Tata Memorial is widely recognised as the face of Indian cancer care. It hosts a World Health Organization (WHO)-affiliated regional cancer registry hub. In its packed corridors and OPD waiting rooms, despair and hope intertwine. According to the National Cancer Registry, 70,000 to 75,000 new patients arrive annually from across India at Tata Memorial — and that is possibly the reason why Dr. David Kissane, a pioneer in psycho-oncology who started work in the field in the 1990s at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, points me to its psycho-oncology department. There, Dr. Jayita Deodhar and Dr. Savita Goswami, who were limited by time and permissions from the management to be interviewed, work with thousands of patients every year.

The Old Tata Memorial Cancer Hospital at Parel.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Kissane, who has been a president of the International Psycho-Oncology Society in the U.S., and has written for its Psycho-Oncology Journal, says, in the first half of the 20th century, cancer was feared as a death sentence and talking about it was taboo. As its treatment with surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy could be debilitating and disfiguring, attention was drawn to the psychological responses and how to optimise coping.

The need for cancer therapy

After 70-year-old Abhimanyu Pandye, a resident of Chauri Chaura in Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, came to Mumbai’s KEM Hospital for treatment of his late wife’s advanced stage breast cancer in 2018, he and his family were navigating grief, distress and unfamiliarity. For surgery and chemotherapy, Pandye shifted her to Nair Hospital to be treated by a specialist, where he met psycho-oncologist Rita Shah. The consultant, who works with several government hospitals in Mumbai, was the only psycho-oncologist at Nair Hospital at the time.

“Everything about cancer was so confounding to me,” he tells me over the phone. “The support from her was everything at the time. I learnt what was really going on with my wife’s body, how to talk to her, how to console myself from the grief of my wife’s suffering. I learnt how to accept that her future was uncertain. I continued to be in touch with her even after my wife passed away. I couldn’t have done well in the unfamiliar big city without Rita Shah’s advice and support,” Pandye says.

According to the 2025 study ‘Psycho-oncology in India’, published in Journal of Cancer Policy, a narrative review of psychosocial cancer care studies in India (2000-24) reported distress in 22%-62% patients, with the highest being in head and neck, and breast cancer. In an earlier 2021 mixed-method study in Indian Journal of Palliative Care, patients reported moderate to extreme distress (53.5%) with low referral/utilisation of psycho-oncology services (8.6%).

At Adyar Cancer Institute, Chennai, Dr. Divya Rajkumar points out that when she joined work as a psycho-oncologist in 2018, it was a new field in India. “It is still new, but we are seeing results. I have seen patients transform after going through sustained therapy during cancer treatment — even patients with terminal disease. Just to continue treatment and live becomes a challenge. For parents of paediatric cases especially, psycho-oncology can be very powerful. We also work in group settings, with patients’ and survivors’ support groups.”

For parents of paediatric cancer cases, psycho-oncology can be very powerful.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Dr. Rajkumar’s job includes evaluating a patient when they get admitted for surgery or chemotherapy, and then using treatment modalities that would help them specifically, such as CBT or sometimes just psycho-education. “We have various ways to evaluate, including the use of a Distress Thermometer in hospital settings to measure their level of distress during treatment,” she says. Today, she is one of seven psychologists in the hospital’s psycho-oncology team.

For patients who want to go that extra mile, therapy often comes in the form of survivors who are living fulfilling lives after cancer. Actor Tannishtha Chatterjee, in remission after Stage 4 metastatic breast cancer, told me in between rehearsals for her play Breast of Luck, at G5A auditorium in Mumbai, “I haven’t been to formal counselling, but what I have got as emotional and mental support from friends, colleagues and survivors, keeps me going. My therapy comes from my circle of sisters.”

During one of my first conversations with Vijay Bhat, he persuaded me that the first step to accepting a cancer diagnosis is to be able to embody this belief: “My cancer is me.” Bhat is optimistic about the future of psycho-oncology. “This is a tacit recognition of the fact that the mind and body are indeed connected. It’s great news. The key insight is that immunity is our best line of defence against the occurrence and recurrence of cancer. Immunotherapy is the great new frontier of cancer treatment, which basically strengthens the body’s immune system to fight the cancer. Whatever can strengthen and optimise immunity, and we know that happens when we address the whole spectrum of physical, mental, emotional, relational and spiritual aspects, is worth doing.”

Dr. Aju Mathew, who works at Ernakulam Medical Centre, Kochi, says patients are beginning to realise the need for help in coping with their mental-emotional difficulties during their cancer treatment. “Patients are asking for counselling. But for psycho-oncology to become more popular or sustainable, it needs government endorsement and certification. It has to be universally accepted as an integral part of cancer treatment. To sustain departments, we need staff, infrastructure. But in my view, the in-hospital setting is not the best for psychological counselling. A cost-effective and patient-friendly model for psycho-oncology is virtual clinics. Patients pay less, and they get the counselling in the comfort of their home. That should be our future model for psycho-oncology,” Dr. Mathew says.

A cost-effective and patient-friendly model for psycho-oncology is virtual clinics.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Anybody gripped by cancer has this question uppermost on their minds: why me? After nine years in remission, I still grapple with it. I’ve been a guinea pig in post-cancer “inner healing”, and finally gravitated to sustained trauma-informed therapy and ancient spiritual practices.

Over five years, I felt a shift in overall health and immunity when I found a sense of control and direction over my health and life. When you realise and accept that you could die in a few months or years, you will really live during that time — that’s the light.

The writer is a Mumbai-based journalist and health advocate, a cancer survivor, and behind the preventive health and longevity media IP, @the_slow_fix.

Discover more from News Link360

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.