Inside Ballia’s bindi-making network, led by women’s groups

The result is a product that moves through weddings, temple visits, local markets, and exhibition stalls, while quietly supporting a chain of livelihoods driven largely by rural women and steady handwork.

One of the people organising this work is Geeta Verma, a resident of Gadwar in Ballia. Since 2017, she has been linked to bindi production through a women’s self-help group, helping turn what was once scattered home-based activity into a coordinated source of income.

Ballia’s bindi work has also gained visibility through the state’s One District One Product (ODOP) programme, which has created clearer pathways for local producers to reach wider markets.

From entry to enterprise

Verma did not come from a business background. She recalls a period when she was not engaged in steady work and spent most days around home. A visit to the district industry office changed that direction.

Encouraged to explore a product-based livelihood, she studied bindi-making and felt it was a skill she could learn and grow alongside other women.

After a short training programme outside the district, she returned and began training others. The work, she explains, uses simple steps but demands precision.

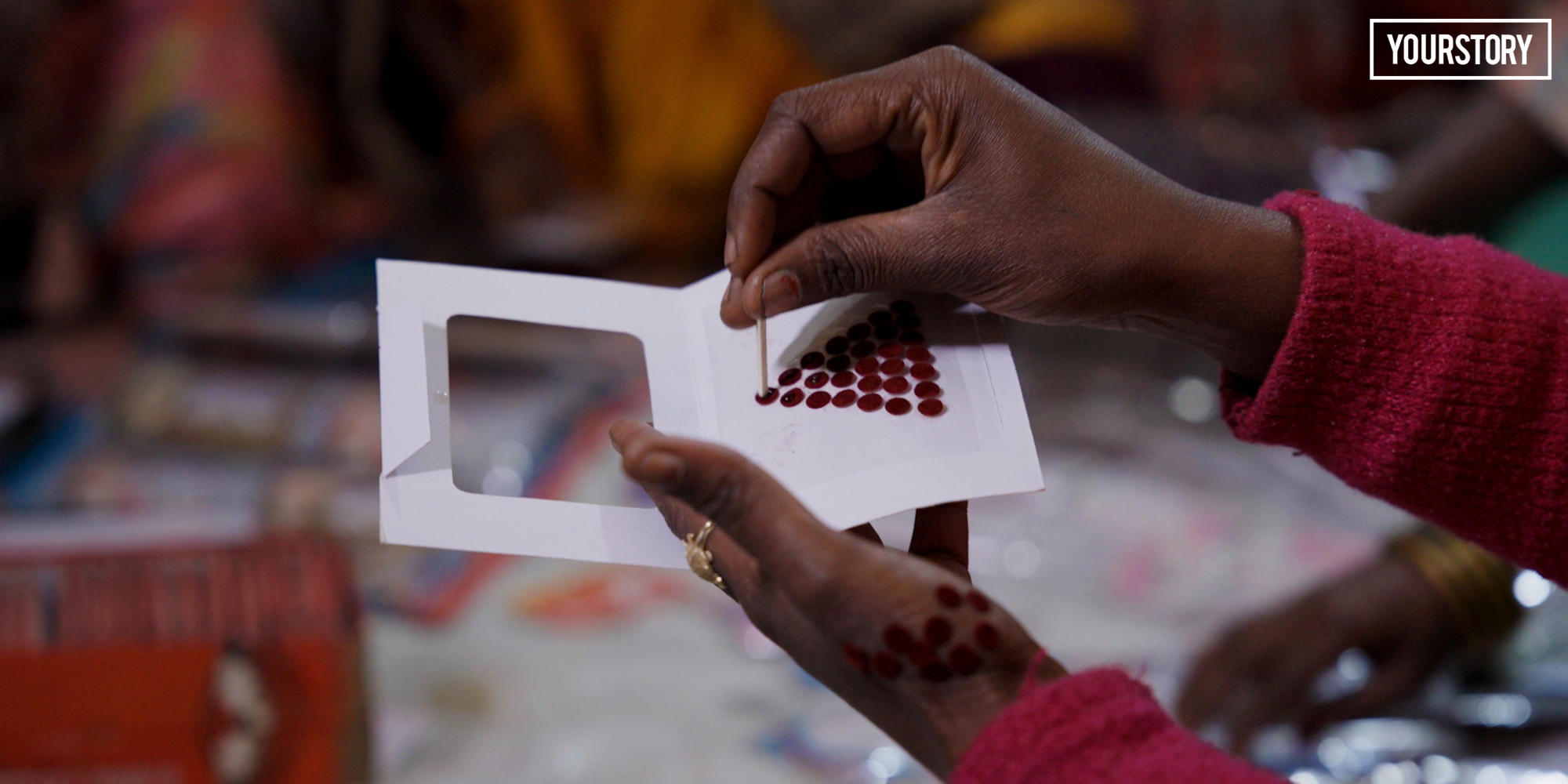

Bindis are made from prepared sheets that are cut into shape, mounted on cards, pasted using adhesive, and then decorated. The same base can lead to very different outcomes depending on the finish, from basic single-piece bindis to stone-studded designs meant for festive wear.

In the early days, only a few women were willing to join. Many were unsure if the effort would translate into reliable earnings. Over time, as orders became more regular, participation expanded.

Today, women from villages such as Nagra, Gadwar, Rachhad, Jigani, Khadsara, Khejuri, and Sukhpura are connected to the work through her Parvati Mahila Self Help Group.

Making, markets, ODOP

The daily routine follows a steady rhythm. Women typically begin work by mid-morning and continue until evening, either from Verma’s workspace or from their homes.

Quality is judged by neat cutting, firm pasting, and careful decoration that holds its shape by the time it reaches buyers. Storage also matters, since finished bindis can lose form or shine if they are packed poorly or exposed to heat and dust.

ODOP support has helped the group improve market access. Verma says exhibitions and fairs have allowed them to sell directly, while also connecting with traders who place repeat orders.

Toolkits provided under the programme, including basic furniture, storage units, mats, and hand tools, have helped make the work more efficient and organised.

For many women, participating in exhibitions brings more than sales. It creates confidence that the product can travel beyond village markets, and that their work has a real buyer base.

As demand grows, Ballia’s bindi-making continues to sit at the intersection of craft and opportunity, creating steady employment through small, careful units of work repeated every day.

Discover more from News Link360

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.